Europe’s sustainable finance crossroads: Will SFDR 2.0 close the transparency gap?

The European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) recently released their 2025 Annual Report on Principal Adverse Impact (PAI) Disclosures under the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). While the report highlights notable progress on PAIs disclosures, particularly among larger financial institutions, it also exposes persistent gaps in methodology, comparability, and investor relevance. While it is necessary to point out these gaps, it is also important to note that the PAI template at entity-level is defined by the ESAs as those gaps have not been addressed by the various FAQs that were issued by the ESAs since the SFDR’s inception.

As SFDR 2.0 is expected to be issued by the European Commission soon, a pivotal question emerges: should PAI disclosures remain focused on the entity-level reporting, or should the regime pivot towards product-level transparency?

Entity-level progress: A step forward… but is it in the right direction?

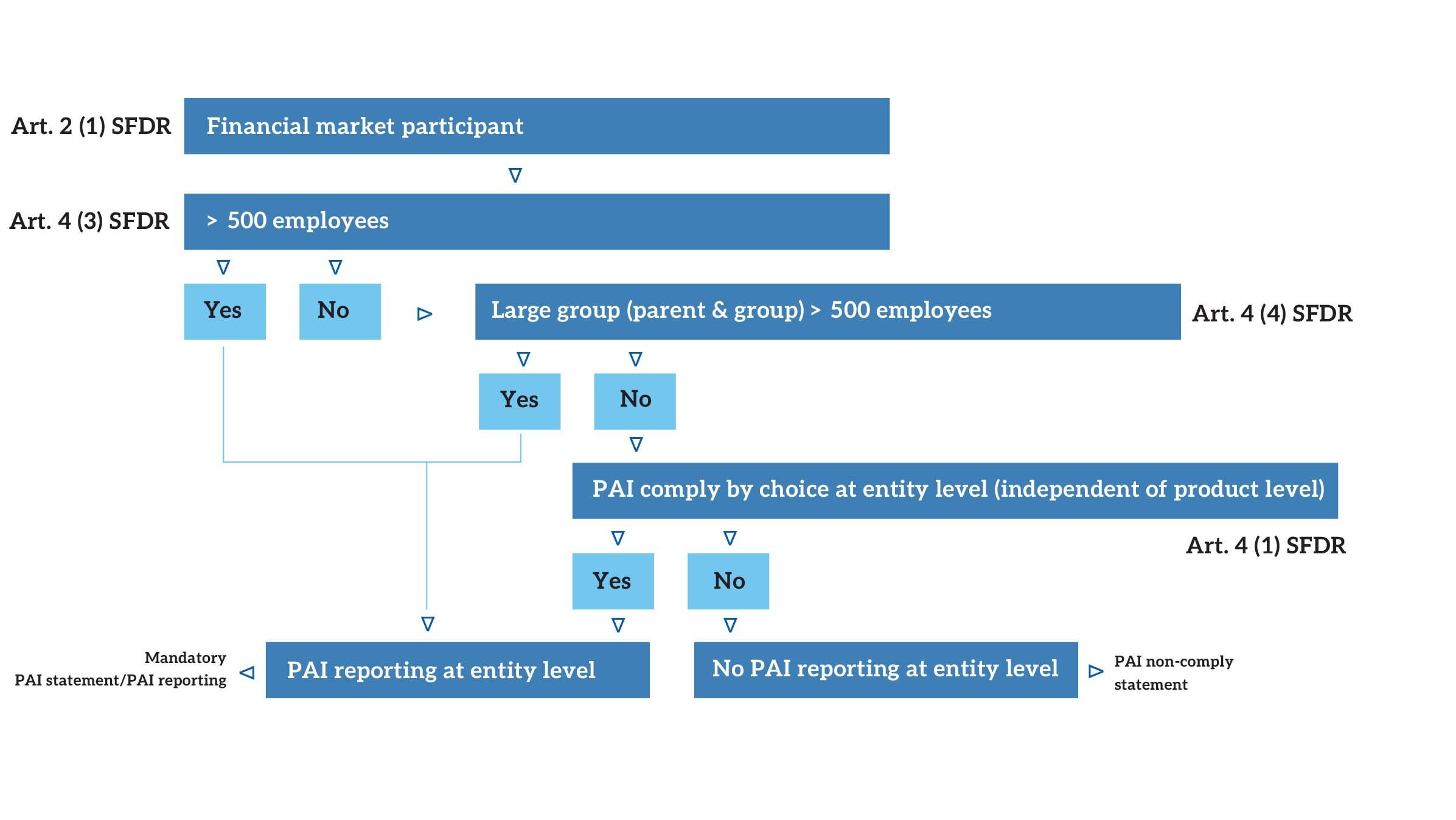

The requirements for PAI reporting at entity-level are not mandatory for all financial market participants (FMPs). As Figure 1 below shows, and as demonstrated by PwC’s first study on PAI statements, only FMPs that have more than 500 employees are required to report on their PAIs at entity-level.

Scope and obligations of entity-level PAI statements

Source: PwC Luxembourg. Mind the Gap: Principal Adverse Impact Statements in the AWM Industry

The ESAs’ report for PAI statements published by June 2024 shows that many PAI reports – and most are voluntary PAI reports and not mandated under SFDR – remain incomplete or inconsistent, with some blurring the line between factual reporting and promotional language.

Whereas these observations are providing a fair representation of the state of entity-level PAI reporting overall, they are not new and are (partially) a result of the template that is provided under SFDR Level 2 which has received limited additional guidance in the ESAs’ Q&As since its inception. Comparing PAI statements from one FMP to another is simply not possible as the FMPs are not even required to disclose on a mandatory basis the proportion of assets under management that are covered within the entity-level PAI statements

The current inconsistencies in entity-level PAI reporting raise a broader question about coherence and efficiency. If, as many policymakers propose, entity-level sustainability data is eventually housed within the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) framework, then continuing to enforce Article 4 disclosures under SFDR (i.e. entity-level PAIs disclosures) may on the one hand risk duplicating reporting obligations. On the other hand, the CSRD scope (the debate is to this date still focused on number of employees with 1,000 seemingly being the lower possible boundary) and the entity-level PAI reporting scope are materially different today.

Product-level disclosures: Where investor decisions are made

Product-level sustainability disclosure (i.e. Article 7 of the SFDR) offers the most actionable insights for investors, aligning with how capital is actually deployed. Whether comparing ESG equity funds or evaluating the impact profile of green bonds, investors need clarity at the fund or instrument level. While an asset manager’s overall sustainability credentials remain relevant, investment decisions are ultimately shaped by the characteristics of individual products.

Greenwashing risk also tends to manifest at the product level, where marketing claims must be substantiated by actual investment strategies and outcomes. Strengthening disclosure requirements here directly enhances transparency, comparability, and investor protection.

This is especially relevant given the ESAs’ own findings that many firms that opt out of entity-level PAI consideration still market Article 8 or 9 products. Without robust product-level data, investors are left navigating a landscape of ESG claims with limited substantiation.

On the other hand there might be different drawbacks of limiting PAI disclosures to the product-level and not mandating or at least allowing the option to report at the entity-level. Drawbacks may include (i) heightened greenwashing risks and limited accountability at the entity level as firm marketing campaigns are out of touch with overall firm results, as well as (ii) limiting the understanding and analysis of ESG information and their potential impact on financial returns and performance at firm level.

See also: What comes next for SFDR: Final recommendations and a future in the balance

SFDR and CSRD must be complementary

The current overlap between SFDR and CSRD creates structural inefficiencies. Firms subject to both frameworks face potential duplicative reporting obligations, increasing compliance costs and complicating the information available to investors.

A clearer division of labour may emerge as a preferred solution. CSRD can anchor entity-level sustainability reporting, offering a standardised framework for corporate ESG data. SFDR, in turn, can focus on product-level disclosures, ensuring that investment products are assessed on their own merits.

This alignment would streamline sustainability reporting, reduce duplication, and improve the usability of ESG sustainability data.

On the other hand, entity-level PAI reporting may provide more value going forward for investors and supervisors, if clearer requirements and alignments with CSRD concepts would be put forward. This may inter alia include (i) the acknowledgement that not all principal adverse impact indicators are material for all investments, (ii) clarifications that an FMP is not expected to improve PAI results for products that have not received such a mandate from investors, and (iii) ensuring comparability by requiring disclosure of covered assets under management proportions as well as allowing specific disclosures for asset classes/investment strategies. Ultimately, such clarification would lead to simplification.

See also: What to expect in SFDR overhaul

SFDR 2.0 and the road ahead

The European Commission’s SFDR 2.0 consultation has opened the door to a reimagined framework. Proposals, such as the ones presented by the Platform on Sustainable Finance in late 2024, include replacing the Article 6/8/9 quasi-classification with four new categories, or labels: Sustainable Products, Transition Products, ESG Collection Products, and Unclassified Products.

Transition products, for instance, are designed to support the shift to a low-carbon economy, even if they do not fully meet the criteria for sustainable products. These may include investments in companies or technologies that are not yet taxonomy-aligned but are demonstrably moving in the right direction. This nuanced category recognises the importance of financing credible decarbonisation pathways without excluding assets that are essential to the transition.

This shift would require more granular product-level disclosures, including alignment with environmental objectives, social safeguards, and taxonomy thresholds.

If adopted this way, SFDR 2.0 could mark a turning point, moving away from broad ESG labels and toward a more rigorous, data-driven disclosure regime.

The road ahead may be long and winded as unpacking and repackaging an existing framework will lead to uncertainty in the market. Uncertainty must be met with clear and pragmatic answers by the European Commission and the ESAs in a timely fashion to reassure FMPs that there is a level playing field and stability within the framework going forward.

Anchoring SFDR where it matters most

While the ESAs’ 2025 report reflects meaningful progress, it also undoubtedly highlights the limitations of the current approach. The current design of the entity-level PAI disclosures, while valuable, are not sufficient to guide investor decisions or prevent greenwashing. As the EU moves toward a more coherent sustainability reporting framework, product-level PAI disclosures (for material PAIs) may become a cornerstone of SFDR 2.0.

From a supervisory standpoint, focusing on product-level disclosures enables more targeted oversight. Regulators can better assess whether sustainability claims are substantiated, reducing enforcement burdens and improving market integrity. This shift also aligns with broader EU goals of harmonising sustainability reporting across sectors

The choices made in the next phase of SFDR reform will determine whether sustainable finance continues to evolve, or risks losing credibility in the eyes of the market.